How would an attempt to wipe out your language affect you? How would it affect your children, and future generations?

For Indigenous peoples of Canada, this question is no abstract thought experiment, but a living reality—one of the most harmful and far-reaching impacts of the Indian residential schools, many of which were run by the Anglican Church of Canada. In the aftermath of what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called an act of “cultural genocide”, survivors faced the challenge of preserving their traditional languages and ensuring the survival of their cultures.

The question of how families coped with language loss and worked to keep their languages alive is the focus of a new project spearheaded by the EagleSpeaker Community Connection Society in Calgary, Alta. Indigenous Language—Strengths and Struggles seeks to create a “free, graphic novel-inspired, educational, multimedia resource” that explores language restoration as an intergenerational impact of the residential school system, based on interviews with more than 200 survivors and their families from the Blackfoot Confederacy.

As part of its focus on language restoration, the Anglican Fund for Healing and Reconciliation recently donated $10,725 to support the project.

“There aren’t a lot of language resources out there, especially [for] Indigenous languages,” project director Jason EagleSpeaker said. “Now that we’re getting into 2017, they’re coming about—there are apps and all that. But one thing I didn’t feel was really being addressed was why Indigenous language thrives in some families, but not in other families.”

Currently one-third of the way through his initial research, EagleSpeaker is now storyboarding the illustrated version of individual and family language stories for the resource, which will present the stories in a comic book-style format.

A website scheduled to launch in September will feature all the language stories alphabetized according to name, with links to biographies of participants and illustrated versions of the stories if available. An e-book version will also be available for download as a PDF file, which can be printed or sent through email. The project is an ongoing initiative, and new language stories will continually be incorporated.

Strengths and Struggles emerged from a previous project EagleSpeaker conducted on the impact of the residential school system. While conducting interviews with survivors, he found a common theme of language loss being one of the biggest obstacles people were trying to overcome.

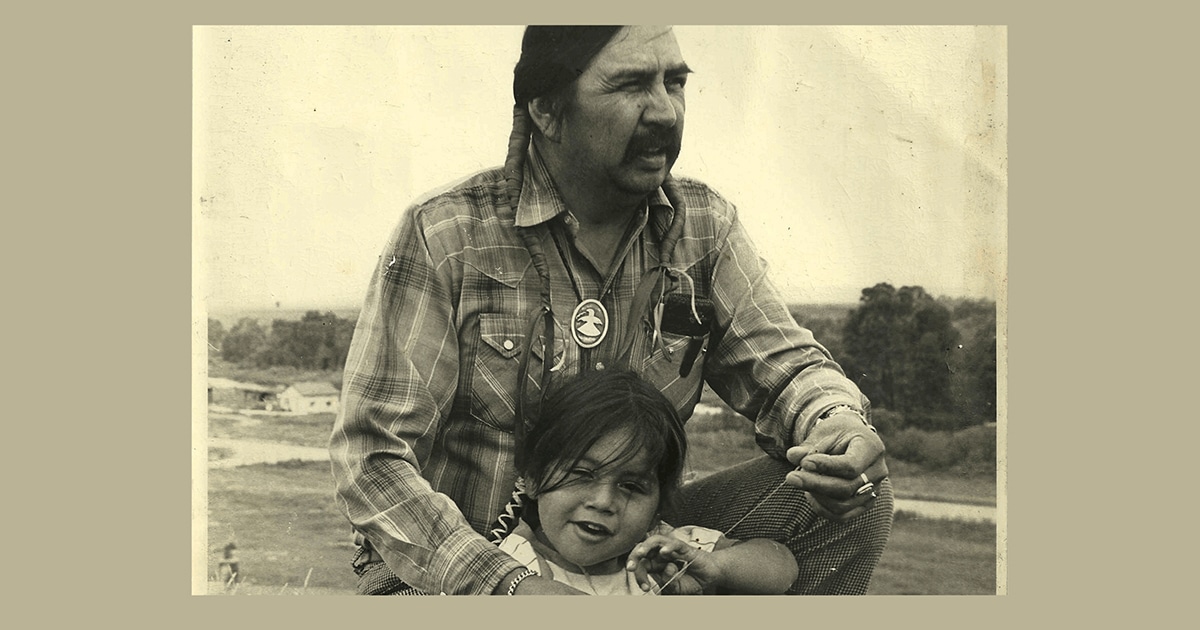

That theme struck a personal chord for EagleSpeaker as a survivor of intergenerational trauma. His own parents and all nine of his mother’s siblings attended St. Paul’s Anglican Residential School near Cardston, Alta., where they were forbidden from speaking their native Blackfoot language.

“My mother came out, I guess you could say, with the best attitude from the whole residential school experience, and she was able to shield that [trauma] from me,” EagleSpeaker said. “But the rest of my family, and my uncles and my aunts, they suffered immensely.

“None of us know our language. I wanted to learn my language as a child. I wanted to speak it, and it wasn’t possible because it was stripped from us. We didn’t have a language champion in our family.”

The concept of a “language champion” is a common factor EagleSpeaker discovered in the course of his research for Strengths and Struggles among families that had managed to continue speaking their traditional languages. These champions made clear to their families the importance of preserving their language and ensured that every family member followed suit.

“If … [the language] does stay alive and it does survive that residential school era, it really almost comes down to a few individuals in the family that have kept it going … and also have fluency in their language,” EagleSpeaker said.

EagleSpeaker first began talking to residential school survivors and their families in the traditional lands of his own Blackfoot community, which span virtually all of southern Alberta and a large part of northern Montana. He often gets responses and language stories from other First Nations far beyond Alberta, and plans to expand the scope of the project over time.

The goal of the project is to provide a resource for all audiences who will be able to use it as they see fit—from educators looking for accessible learning resources, to elders and residential school survivors seeking acknowledgement of their experiences, to students and youth wanting a convenient and interactive way to learn about language restoration and the legacy of the residential schools.

The Anglican Healing Fund grant has played a vital role in research thus far by helping cover the cost of honoraria, meals, travel, and accommodation. The capacity of researchers to speak to individuals within their comfort zones—by meeting them in their homes, at community events, over a meal—enables them to hear language stories in an organic and effective manner.

“Something like the Healing Fund allows for those sort of things to happen, because a lot of the other funding opportunities … are so focused in on certain expenditures and them being done in a certain way that it would limit a project like this,” EagleSpeaker said.

“It would limit the grassroots engagement, and it has … Any other types of grants that we’d try to fit into there would impact the integrity of the end result. So thank goodness for the Healing Fund, man. Thank goodness.”

Interested in keeping up-to-date on news, opinion, events and resources from the Anglican Church of Canada? Sign up for our email alerts .