The following marks the third instalment of our report on Justice Camp 2016. Read parts one and two.

I soaked in the sights of Havana as the Anglican Video crew and I drove to meet the Justice Camp economic justice immersion group on the morning of Wednesday, May 4. One of the most distinguishing features of Cuba is the almost total lack of advertisements in public space, which instead feature political billboards and graffiti celebrating the achievements of the revolution.

Our destination this morning was the Colony, a former psychiatric hospital that had been transformed into a shelter for elderly homeless men, euphemistically referred to as “friends of the street.” Some were formerly beggars; others have no families to care for them. A number suffer from illness or disease, the precise identity of which they did not know for lack of a medical history and treatment. The main goal of the facility is to offer love and care to the residents.

Dr. Francisco Mouza, director of the facility, spoke candidly to Justice Camp participants about the gap between the current state of the facility and its lofty goals as it tries to find the funding for extensive renovations.

Staff members hope to be able to admit up to 200 residents after rebuilding, including elderly women as well as men, with half living there permanently and half staying only during the day and going home at night. They plan to build individual rooms to give patients greater privacy, as well as instilling positive values in unattended children of residents by creating a space called Schools of Peace.

The local community has close ties with the Catholic Church, which often promotes interfaith prayer. A former palace nearby hosts a Christmas banquet each year where hundreds of people attend.

Though the Colony—which staff members hope to re-name—is not run or owned by the church, Dr. Mouza noted, as interpreted by a translator: “This friendship with the poor has allowed us to live out the gospel in a very concrete way.” The experience of service, he added, has changed the lives of members of the community.

Touring the facility, we saw large dormitories where elderly men in their beds watched as we passed by. Rooms that were once dungeons have now been renovated and turned into infirmaries. Flies flew around a Spartan dining room near the kitchen. A future pig pen could be seen in the back of the facility.

Despite the rough conditions, the obvious care and concern of the staff for the residents was evident, as we witnessed in a dramatic moment when they sprinted across the yard to prevent an elderly man in a wheelchair from falling.

Canadian participant Annalee Giesbrecht, a member of St. Margaret’s Anglican Church in the diocese of Rupert’s Land, compared her experience at the Colony to lectures her group heard the previous day on Cuba’s changing economic environment.

“It seems like here at the Colony, they obviously have a lot of difficulties that they’re facing, like lack of funding and a building that is badly in need of renovation,” Annalee said.

“But I see the same kind of hope that people talked about in the lectures that we had yesterday. I don’t know if it’s related to the changing economic system, or just … a general hope that things will get better. But it seems like there’s a lot of optimism.”

For more than an hour afterwards, I enjoyed an impromptu domino tournament with Justice Camp participant Alicia Archbell, volunteer for youth events and social justice initiatives with the diocese of Niagara and PWRDF diocesan ambassador, and two Colony residents.

The sense of fun was contagious, with one of the residents singing along to the radio as we played. In a likely case of beginners’ luck, the Canadian team won two consecutive rounds against the Cubans who kindly taught us the rules of the game.

During lunch, Alicia and Cuban participant Galier Hernández Basulto, youth chair at the Episcopal Church of El Buen Pastor in Esmeralda, spoon-fed two residents who were immobile and confined to their chairs.

“They were [two] exceptionally different experiences,” Alicia said of her morning at the Colony. “The dominos was sitting around with people who count way faster than I can … just sitting around having a good time, even though the language barrier was there. You had socialization and just fun and giggles.

“[Then] in comparison, I went and ended up feeding someone who was very ill … Just having that kind of compassionate, empathetic moment … I was able to see the fact that [staff members are] helping everyone, no matter their mental [or] physical abilities.”

After lunch, I departed with Anglican Video to rendezvous with the social engagement immersion group of Justice Camp in Varadero.

The next morning we re-joined the economic justice group and accompanied them to a ramshackle Havana neighbourhood, where Cuban church members had created a project to improve the availability of animal protein in the diet of area families by raising a diverse group of animals including goats, chickens, and rabbits.

The church had recently bought equipment such as an incubator, oven, and mixer for animal feed. The project has garnered the support of the local community as it providing continually increasing output in products such as eggs, while also hosting gender workshops to promote the participation of women in managing the project.

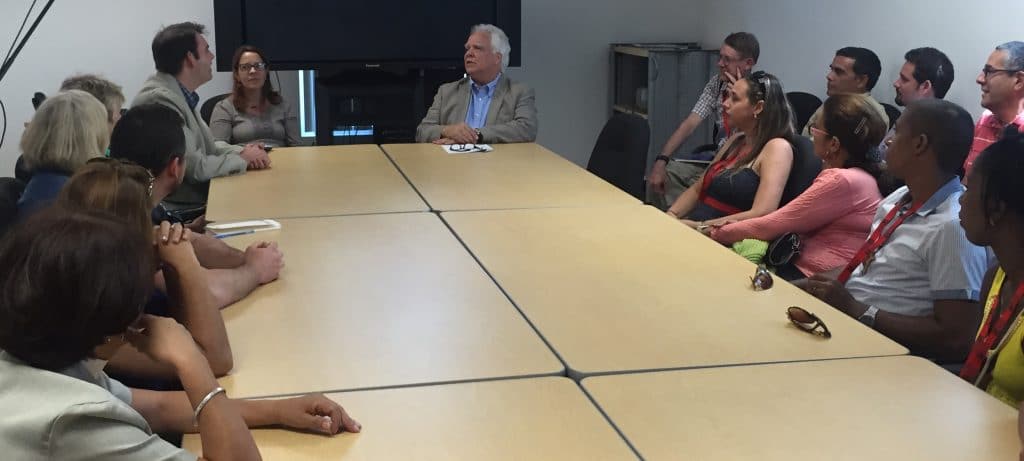

That afternoon, members of the economic justice immersion group met with Ambassador Yves Gagnon at the Embassy of Canada in Cuba. Flanked by the program officer for the cooperation agency, the Canadian ambassador discussed the bilateral relationship between Canada and Cuba. Gagnon suggested that the two countries were entering a good period of relations, illustrated by the recent visit to Cuba by Minister of Foreign Affairs Stéphane Dion—the first such visit since 1995.

Reflecting on the immersion group’s experiences, Cuban participant Gil Fat Yero, lay minister for the congregations of San Marcos (Holguin) and San Andres (Manati), highlighted how they were able to directly see many aspects of Cuban life and the different ways that churches are helping entrepreneurs and communities.

“We had the opportunity to see people creating their own projects … It was God’s gift, because through all the things, we could see the hand of God acting through his people,” Gil said. “I think that was the most important thing.”

Read part four of the report.

Interested in keeping up-to-date on news, opinion, events and resources from the Anglican Church of Canada? Sign up for our email alerts .