View a PDF version of Highlights from the Council of General Synod: November 8, 2019.

Council members gathered after breakfast at 8:45 a.m. at the Queen of Apostles Renewal Centre in Mississauga.

Morning Eucharist

Members of the Council of General Synod (CoGS) gathered for the morning Eucharist. National Indigenous Anglican Archbishop Mark MacDonald provided the homily.

Orders of the Day

The Rev. Monique Stone, co-chair of the planning and agenda team, read out the Orders of the Day.

Strategic Planning Process

Judith Moses, a member of the Strategic Planning Working Group, spoke to the council on what the process for developing a new strategic plan to succeed Vision 2019 will look like. Though the group has not formally met yet, she wanted to give CoGS an idea of the next steps they will take.

General Synod 2019 provided the mandate for the Strategic Planning Working Group with Resolution A-103, which directed CoGS, in partnership with the entire church, to prayerfully undertake a strategic planning process that would lead to the presentation of a proposal at General Synod 2022. Its mandate also includes addressing Resolution A-102, in collaboration with the Governance Working Group, which directs CoGS “to develop and initiate a process to re-examine the mission of General Synod in relation to the dioceses and provinces, including the self-determining Indigenous Church, with a goal to allow the structures of General Synod to best enable and serve God’s mission.”

The proposed theme of the new strategic plan, Moses said, is the same theme of the triennium: “A Changing Church, A Searching World, A Faithful God.” In its approach to the strategic plan, the working group is adopting what it describes as a more “realistic” timeframe of six years, rather than the 10-year-period for Vision 2019. Ten years, the group determined, is too long for such a period of rapid change. The working group hopes to develop an “evergreen” document that can adapt to change, based on modern management practices to better support CoGS. They aim for the strategic plan to provide accountability of results, performance measures for progress on milestones and a method for assessing risk management. Assessing outcomes from Vision 2019 will also be a key element.

The Strategic Planning Working Group has outlined what it describes as “transparent shared principles” to guide its work. They hold that the process for developing a new strategic plan should be consultative and engagement-based, a “journey together across the church” that will include walking beside the Indigenous church. The process must model ideal behaviour, such as partnership, deep listening, working with diversity and inclusion, respect and embracing the changing world. Group members will seek to use best practices in the field of strategic planning, based on progress achieved in Vision 2019. The process will be based on priorities reflected in resolutions from General Synod 2019, realistic and practical in the context of a changing church, and will include spiritually-based deliberations on shared gospel teachings.

In moving forward, the working group will rely on key assumptions, which can help ground the planning process within a changing environment. Examples might include:

- The Indigenous ministry and self-determination are central to the identity and operations of the entire church.

- Church’s fiscal situation is likely to continue to decline.

- Youth are the lifeblood of the church and strategies to engage youth are a priority.

- New governance processes, structures and operations are central to achieving strategic goals.

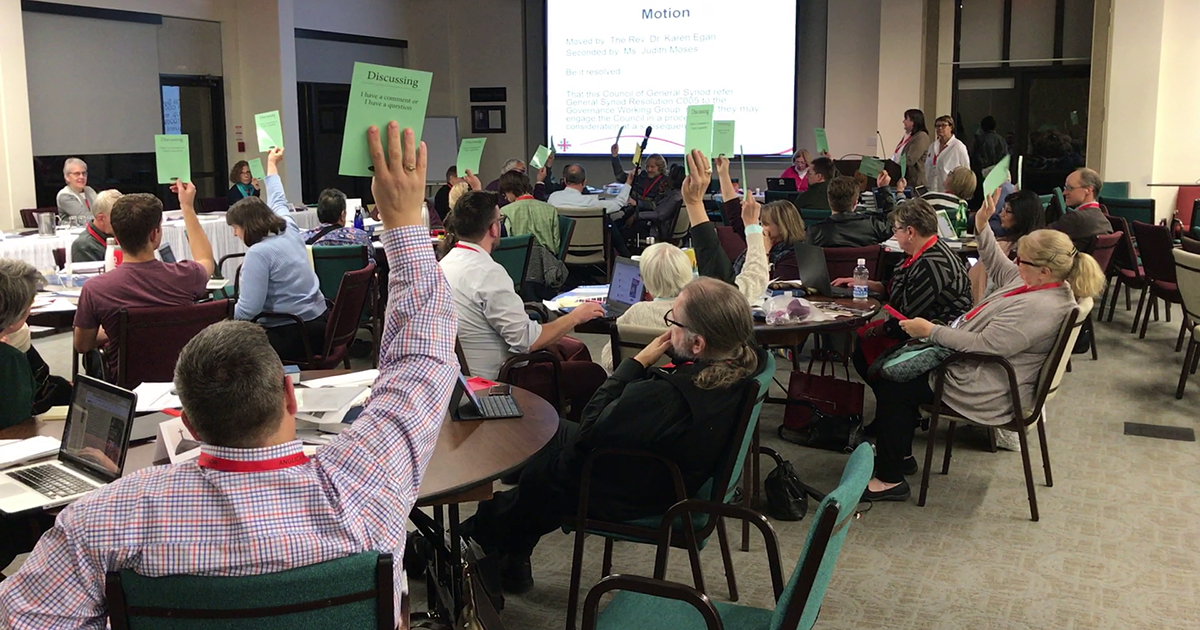

The process for putting together a new strategic plan cannot happen without consultation, Moses said. In that spirit, she put forward a motion to the council, which was carried.

Resolution

Be it resolved that CoGS hereby affirm the Primate’s appointment to a Strategic Planning Group further to Resolutions A-102 and A-103 directing the undertaking of a strategic planning process. Appointments will include: Judith Moses (chair), Monique Stone (co-chair), Cynthia Haines-Turner (past prolocutor), Ian Alexander (past chair, Journal working group), Dale Drozda and Valerie Kerr (officers of General Synod), as well as the Primate and General Secretary as ex officio members.

Moses concluded her presentation by asking three questions of council members regarding Resolution A-103:

- What is your hope for a strategic plan to guide the church to 2028?

- What would you like the plan to be able to do?

- What do you hope the plan will inspire in the church? How will it be useful to dioceses, parishes, Church House, the Indigenous Ministry?

She encouraged council members to email members of the working group with responses, and said CoGS would revisit these questions through table group discussions later in the day.

Members broke for coffee from 10:15 a.m. to 10:45 a.m.

Racial Justice

Archbishop Linda Nicholls, primate of the Anglican Church of Canada, reminded council of her remarks the previous day asking the church to focus on dismantling racism. She noted that the church has been committed for a long time to its Charter for Racial Justice in the Anglican Church of Canada, approved by CoGS in March 2007. However, the primate suggested that the principles of the charter have not moved from the national level more deeply into the hearts and life of the church. At each CoGS, members are asked to sign the Charter for Racial Justice and pledge their commitment to its principles.

The primate said she had asked a small group of Church House staff to meet with her and ask how the church can be more proactive in its work to dismantle racism. She expressed her deep gratitude to Archbishop Mark MacDonald for his voice in “pointing out racism that is embedded in our culture and church, but doing it in a loving, gracious way that invites us in.” Such eloquence can be a significant attribute when discussing a topic in which people can become defensive, she said, inviting MacDonald to address the council.

Archbishop MacDonald began with two stories to explain what he wanted to say about racism. The first stemmed from his time as rector of a multiracial, multicultural church in Portland, Oregon, which had a number of African-American families in it. One of these families lived in a mixed-race neighbourhood and included a boy who was five years old. The mother once related to MacDonald how she had been driving around the neighbourhood with her son when he saw a “neighbourhood watch” sign with an ominous black figure on it. Her son asked, “Mommy, is that because we live here?” The woman was “devastated,” MacDonald said, because the boy, “already at his tender age, internalized negative stereotypes about who he was and about his identity, and I think this is an important thing to understand.”

The second story involved an Indigenous church leader in Fort Defiance, Arizona, who had been a member of the American Indian Movement and an activist on Indigenous rights. MacDonald had been sitting in the Phoenix airport with him waiting to catch a flight, when the church leader pointed to a counter and said, “Do you see that? The closer we get to home, the more tattered everything is. We destroy everything.” This man, MacDonald said, “described basically his disgust at who he was. Even though he was, I would say, a very strong advocate and activist, he had internalized the hatred that has been projected upon him.”

The national Indigenous archbishop suggested that popular understandings of racism tend to misunderstand the issue. “Nobody in our society wants to be called racist,” MacDonald said. “I was watching a documentary on the Ku Klux Klan, and they don’t want to be called racist,” he added to laughter from the council. “If the bar is that low, pretty much no one is a racist…. Donald Trump says that, Joe Biden says that, Justin Trudeau says that…. It seems to me that if somebody says, ‘I’m not a racist,’ they don’t understand what racism is.”

Racism, MacDonald said, is a systemic issue that affects everyone, to the point where even someone who is a member of a racial minority can internalize the negative stereotypes by which this system characterizes them. The archbishop drew the attention of council members to the recent book How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi. In this book, Kendi argues that there are two kinds of people in society: “not a racist” and “anti-racist”.

This distinction is “a critical and important thing,” MacDonald said. He described how harmful concepts emerge, such as the racist idea that “Indigenous people are primitive,” and that “with enough education, you too can be like a white person in the suburbs. That’s not the reality.” Ideas such as self-determination often confuse people because they believe the best goal for Indigenous people is to become like the majority—in a word, assimilationism. The internalization of these ideas affects everything from the way the government views Indigenous people, to the way Indigenous people view themselves, to the way the church looks at Indigenous people.

“I’m a racist,” MacDonald said. “If that shocks you, it shouldn’t, based on what I’ve said. And you are too.” The way to health and freedom, he said, is to become an anti-racist, which is the substance of Kendi’s argument. For that reason, MacDonald was excited about the primate’s initiative to dismantle racism.

In conclusion, he suggested that the Bible has a more sophisticated and comprehensive way of understanding systemic evils than those today who view racism simply as “crude and gross talking about people of other races by someone who’s white.” In its analysis of systemic evil, the Bible uses the term “principalities and powers,” which suggests that evil ideas or institutions can move in a way almost impossible to track and work their way into every aspect of human behaviour. In Ephesians 6, Paul says that “We are not wrestling with flesh and blood…but principalities and powers.” The problem of racism is not a personal issue, MacDonald said, but rather a systemic issue, and Paul is suggesting that the heart of Christian discipleship lies in engaging such “hideous, systemic structural evils.”

MacDonald put a question before council members: “Describe a time when you have experienced the impact of systemic racism.” Twenty minutes of table group discussion ensued. At the end of this discussion, Primate Nicholls said council members would be continuing these discussions at each CoGS meeting to familiarize themselves with the concept of systemic racism and to learn how to look for racism within church structures. She anticipated that they would pay particular attention to the self-determining Indigenous church to see if it adopts different structures to Western models. The primate asked members to fill out and sign the pledge to the racial justice charter and said church members would be speaking to bishops across Canada as well as Episcopal Church staff to learn about their respective anti-racism work.

Vision Keepers

Judith Moses, former chair of the Vision Keepers Council, offered an update for CoGS on the council’s work. Though she had recently stepped off the Vision Keepers due to many other responsibilities, she would still be giving the report.

Moses provided background information on the Vision Keepers, originally formed in July 2016 as the Council of Elders and Youth. The council subsequently changed its name to reflect their self-determination and efforts to create a non-Western way of working. The mandate of the council is to monitor the Anglican Church of Canada’s honouring, in word and action, its commitment “to formally adopt and comply with the principles, norms and standards of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP),” and to help the church live out the fourth Mark of Mission: “To seek to transform unjust structures of society, to challenge violence of every kind and to pursue peace and reconciliation.”

The Vision Keepers have developed a framework to assess the church’s progress in supporting UNDRIP and Indigenous self-determination. Elements of this framework include church governance, structures, policies, processes and practices, accountability, structural change, voice and representation, reconciliation and justice, equality, projects and initiatives, and tools. Anglican support for UNDRIP and its focus on Indigenous self-determination will be demonstrated through eight elements:

- Authentic, self-determining governance and Indigenous-defined structures;

- Responsive, Indigenous-driven programming and community-based reconciliation/healing projects that make a difference;

- Stable, sufficient resources supporting Indigenous ministry, including pastoral care;

- Dioceses active and committed to reconciliation;

- Active advocacy at all levels of the church;

- Strong communications/dialogue and learning across the broader church and within the Indigenous church;

- Worship reflective of community, including vernacular; and

- Indigenous church accountable to Indigenous leadership.

In their meetings, the Vision Keepers have made some key observations. Implementing UNDRIP is a journey, one which requires ownership and accountability from the whole church in order to make progress. At the parish level, information on reconciliation is largely ad hoc. New tools are needed to support the Vision Keepers, Indigenous ministry and the broader church at the local level. Engaging youth in reconciliation should be a major priority. Advocacy on Indigenous issues is too low-key, and “change champions” are needed for truly shared, cohesive efforts. Equity in support for the Indigenous church also needs to be a priority.

Moses said the Vision Keepers were pleased at the passage of a resolution at General Synod 2019 that made the Vision Keepers Council a permanent forum to oversee the work of the church in implementing UNDRIP. Current issues of concern include finding new members to replace Moses and fellow departing member Bishop Sidney Black; the church in this case might consider appointing non-Indigenous Anglicans to the council. Renewed efforts advocating new federal laws to enact UNDRIP would also be a focus, and earlier recommendations would be updated given recent progress on Indigenous issues.

Members broke for lunch from noon to 1:30 p.m.

Bible Study

Afternoon Bible study saw CoGS members continuing their discussion of Jesus’s appearance on the road to Emmaus, as related in Luke 24:21-35. This passage continues the story of Jesus appearing shortly after the resurrection to two of his disciples, who initially fail to recognize Jesus until he breaks bread with them. During the Bible study, a slideshow projected on the screen displayed artwork from around the world depicting this episode in the gospel.

Cynthia Haines-Turner, co-chair of the planning and agenda team, closed the study session by leading members in a prayer.

ACIP Presentation

Members of the Anglican Council of Indigenous Peoples (ACIP) began their presentation with a prayer and song led by Archbishop MacDonald, “Blessed Be the Name.” CoGS members clapped and sang along.

Indigenous Ministries Coordinator Ginny Doctor noted that it was customary among ACIP to begin anything they do with the gospel of the day, and Canon (lay) Donna Bomberry duly read out a passage from Luke 16:1-8. The national Indigenous archbishop asked table groups to spend some time reflecting on the most important thing they heard in that gospel reading, and five minutes of table discussions followed. Reporting afterwards on their conversations, ACIP members said they had discussed concepts such as apology, forgiveness and redemption. A table group highlighted concern for the poor.

Canon Murray Still, co-chair of ACIP, reported on the council’s latest meeting in Toronto the previous weekend. ACIP strives to maintain the gospel at the centre of everything it does, and members had daily gospel-based discipleship during their meeting, often returning to the gospel during their time together.

During their meeting, they discussed the amendments to Canon XXII at General Synod, which Archbishop MacDonald has said “helped us to understand that we now have the ability to begin putting some meat on the bones” on the structure of the self-determining Indigenous church. In response, ACIP will be holding a Sacred Circle on June 14-19, 2020 at the Fern Resort near Orillia, Ont. The tentative theme of the gathering is “2020 Visions,” centred in part on Acts 20. Scheduling of the Sacred Circle reflects a desire to begin work immediately on figuring out the structures of the Indigenous church.

Also in 2020, ACIP will be hosting its first youth Sacred Circle from March 15-18 at the Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre in Beausejour, Man. The theme of the youth gathering is “Sacred Beginnings.” Together, young people in attendance will learn about their spiritual heritage. Speakers will discuss family, community and the understanding that “it takes a village and community to raise a child.” Participants will learn about Indigenous spirituality through tools such as talking sticks, drums, and teachings from Ojibwe, Cree and Anishinaabe traditions. Organizers hope youth will return home afterwards to continue their spiritual journeys with confidence.

At the recent ACIP meeting, the national Indigenous archbishop also presented his paper A Pathway of Hope, which serves as a guide to stewardship in Indigenous ministries. Finances and stewardship have become an increasing focus of discussions around the Indigenous church, Still said. The main short-term goal is establishing benefits for non-stipendiary clergy, part of a path that ACIP hopes will open up to eventually providing full stipends.

Other guests at the meeting included Reconciliation Animator Melanie Delva, Judith Moses speaking on the work of the Vision Keepers, and Healing Fund Coordinator Martha Many Grey Horses, discussing work of the fund. Two representatives of the Primate’s World Relief and Development Fund (PWRDF), Executive Director Will Postma and Public Engagement Program Coordinator Suzanne Rumsey, shared reconciliation tools for churches, including a mapping exercise featuring nine trained facilitators who can held lead the exercise across the country. Finally, Primate Nicholls joined and welcomed ACIP members, worshipping together and offering her commitment to deepen church efforts to dismantle colonization and racism. “It gives us great hope that our primate is behind us in this effort,” Still said.

Shilo Clark, youth member of ACIP, presented a video that shared responses by Indigenous Anglicans to two events at General Synod: former primate Fred Hiltz’s apology for spiritual harm inflicted on Indigenous peoples, and the amendment to Canon XXII establishing structures for a self-determining Indigenous church. Clark said that the message in the video was one of happiness, but also hard work. “I stand before you realizing that we are literally forging history.” The meeting of General Synod 2019 had given Indigenous people not only a voice, he said, but a vote as well.

Speaking personally on the apology, Clark added, “It was very moving. Coming from an individual standpoint, I’ve had a hard time accepting apologies sometimes. With an apology comes work. Apologies precede work, and as I watched the video, as I watched the primate’s apology, I saw the sincerity…. I hope everybody here has that same sincerity in their hearts, and that we can forge ahead together as people of the church.” He closed his introduction with a quote from Alfred Tennyson’s poem Ulysses:

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are,

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

In the video, Indigenous Anglicans discussed how deeply they had felt the need for an apology for spiritual harm. The 1993 apology of former primate Michael Peers for abuses in the residential schools, they said, had been significant and appreciated. But many still felt the need for an apology that acknowledged the damage done to their languages, cultures and traditional beliefs by an Anglican church which taught that those things were evil. Many of those in the video described a newfound feeling of freedom after Hiltz’s apology. They expressed happiness that they could undertake efforts to help elders realize that their traditional cultures were not wrong at all, and joy at bolstering the identity of their young people and pride in their heritage and traditions.

The vote for a self-determining Indigenous church provoked similar positive feelings centred around recognition by the wider church. Indigenous Anglicans expressed enthusiasm at the authority they now possessed through Canon XXII to make decisions on their own behalf. One respondent said the self-determining Indigenous church was an answer to their prayers and would help “bring the people into a big family.” Another thought about their parents: “If my mom had heard this when she was alive, I think it would have meant the world to her.”

Following the video, Doctor reiterated that apologies, to be heard and be effective, must be followed by actions. She asked the following questions to CoGS:

- What action can you and others undertake since you heard this apology?

- What scares you about self-determination?

- What do you need to know more about self-determination?

After 10 minutes, representatives from different tables reported on their conversations. One table suggested non-Indigenous Anglicans should take a step back, be ready to offer help when asked, but not interfere as Indigenous Anglicans forge ahead with self-determination. At another table, a member recalled their last diocesan synod which highlighted the importance of land acknowledgements at the beginning of all services, on their church bulletins and websites.

Archbishop MacDonald closed out ACIP’s presentation with the song “Prayer for Peace,” with lyrics based on a Navajo blessing. The primate thanked ACIP for their presentation and encouraged CoGS to look for opportunities to share Hiltz’s apology in their churches and dioceses.

Members broke for coffee from 3 p.m. to 3:30 p.m.

Strategic Planning Process (cont’d)

Monique Stone thanked CoGS members for their email responses to the three questions regarding Resolution A-103 on the strategic planning process. She invited table groups to discuss the questions amongst themselves and then share their responses with the council.

After 30 minutes of conversation, representatives from table groups approached the microphone for their reports. One table said that the strategic planning process had to reflect emotions people are feeling across the church. Part of that involved being positive about the future, not getting dragged down by perceived problems and having a plan that “rediscovers hope.” They suggested that the plan focus on inspiring people to go out into ministry in their communities, rather than bringing people in. Worship is still important, but the church must be focused on discipleship as well.

Another table emphasized that the strategic plan is for General Synod, not a signal for every diocese to abandon everything it’s doing. The plan should show how General Synod can add value to and synthesize everything going on in the church and be useful to all parts. Some table groups suggested that addressing the causes of declining membership would go a long way to helping solve those problems. They underscored the importance of a positive strategic plan that would serve as inspirational and motivational for the identity of Anglicans as a church of Christ. They asked what the national church could do to build capacity in areas that dioceses and local churches do not have the resources for.

Stone thanked council for their feedback and invited members to continue relaying their input via email.

Reconciliation Ambassadors Committee

Melanie Delva, national reconciliation animator for the Anglican Church of Canada, introduced herself and discussed her job title and the idea of animation, which she described as “taking something that might be frozen in time and bringing it to life.” Conversations around Indigenous justice and relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities could be frozen in time—such as a person who might believe that the closing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission meant that the process of reconciliation is finished. Instead, Delva said, the question is how to continue the movement and energy of what the church is trying to live into.

The initial response of the church to UNDRIP was the Primate’s Commission on Reconciliation, Discovery and Justice. Established in 2014, the commission included Indigenous and non-Indigenous Anglicans who sought to examine how the Doctrine of Discovery had impacted “not just the church, but all of us.” In the midst of these conversations, Delva said, it became clear that it was necessary for a network of people on the ground to continue this work. Meanwhile, members of the Vision Keepers Council established in 2016 had separately come to a similar conclusion.

At its 2019 meeting, General Synod had passed Resolution A-180, which directed CoGS “to establish a committee to strategize and guide the ongoing work of truth, justice and reconciliation, including building and supporting a network of Ambassadors for Reconciliation from dioceses and regions.” This network was the subject of Delva’s presentation. The ambassadors for reconciliation, she said, would encompass a mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who would guide and support this work. The task now was to determine what the network would look like and its terms of reference.

The process for establishing the ambassadors for reconciliation would begin with consultation and development, part of which was the engagement of CoGS. In March 2020, Delva hoped to bring a proposal to CoGS for their approval, after which the work of the ambassadors would begin.

In her work as reconciliation animator, Delva said, she had been thinking a lot about stories in the Bible regarding sibling relationships. Christians often refer to “our sisters and brothers in Christ.” Looking at various stories in the Bible, from Cain and Abel to the prodigal son, she noticed a trend. In these biblical tales, poor relationships between siblings are characterized by viewing each other merely as children of the same parents. Good relationships, however, see siblings viewing each other truly as siblings, as brothers and sisters.

Delva put forward four questions to CoGS members regarding the need to find potential candidates to serve as ambassadors for reconciliation. Table groups discussed among themselves the following questions:

- How will you spread the news of Indigenous justice and reconciliation in your area?

- Are you called to be an ambassador?

- Who else can you think of who has passion and gifts in this area?

- What do you think needs to be included in the development of the reconciliation ambassadors?

A period of discussion ensued. In response to questions from CoGS, Delva clarified that there were no prerequisites for being a reconciliation ambassador. The idea is not to have 30 people with one person from each diocese, but rather a smaller group that will help the church in its work of inspiration and education; advise Delva in the work of reconciliation based on what they’re hearing on the ground; and support reconciliation efforts by Anglicans in their dioceses. She encouraged council members to email her with more feedback and to subscribe to the e-mail newsletter Anglican Reconciliation Connections.

Digital Video Archives

Staff members from Anglican Video and the General Synod Archives led a presentation on the digitization of the church’s video archives. Anglican Video senior producer Lisa Barry described the effort as “a story about people, history and memories.”

In the last few years, she said, Anglican Video staff had noticed a marked deterioration of footage in the video library. Attempts to preserve this footage led them to digitization, which has become a popular method for maintaining old video footage by media sources such as the CBC. While digitization itself is relatively simple, naming and organizing the footage is a more difficult task.

Since beginning the process, Anglican Video has digitized the footage from 11 General Synods—every one since 1988—and nine Sacred Circles. To fund the project, they applied for and received a grant from the Ministry Investment Fund. Ben Davies, production coordinator/manager for Anglican Video, explained that the process of digital conversion involves uploading footage from old tapes to a special cloud service, Capsule.

“Why is this project so important?” Karen Evans, former librarian at the church’s national office, said that the last 30 years had seen incredible change and innovation in the structure, culture and policy of the Anglican Church of Canada: the normalization of female clergy, the introduction of a new hymn book, and new relationships with Indigenous Anglicans, to name a few. Researchers from inside and outside the church can obtain much information and background on the actions and outcomes of General Synod using print journals and official statements on the database. However, these are all text-based resources.

Video-based resources have the advantage of being able to capture and record all events at General Synod, not just resolutions. This is significant, Evans said, because for the first time, researchers can see and hear all presentations, education blocks and debates that led to decisions at General Synod—valuable context that can illustrate who spoke to resolutions, how many people spoke, and whether the debate was heated or a mere formality. Viewing old footage can be a “powerful and immersive experience,” which Evans compared to time travel—packing a particular emotional punch when watching church members who are no longer living.

One of the greatest challenges of the digitization project has been figuring out how to reduce the vast material available into records that would be manageable in size and content for researchers. Through painstaking efforts, Anglican Video and General Synod Archives staff identified speakers, wrote descriptions and categorized material.

The benefits of a digitized and categorized video library have already proven themselves in action. General Synod archivist Laurel Parson noted that she had recently been contacted by a man hired to perform with a giant puppet for a presentation at General Synod 1992, who knew he had been videotaped and wished to get a copy of the segment for a grant application. Because the footage had been digitized and described, Anglican Video was able to provide him with a copy of the video. Similarly, family members of the late Vi Samaha, an Anglican from B.C. and residential school survivor who died in 1999, contacted General Synod seeking video of her sharing her story to grandchildren who had not gotten the chance to know her. Again, Anglican Video was able to provide copies of the footage to Samaha’s grandchildren.

The ultimate goal of digitization is to have the entire video database online on the General Synod Archives website so that people can do their own searches, watch clips and ask for copies. The work is still in progress and is not yet ready to go online, but Evans was able to show CoGS the website. Researchers will be able to go to the Archives homepage and view two online collections, Genera