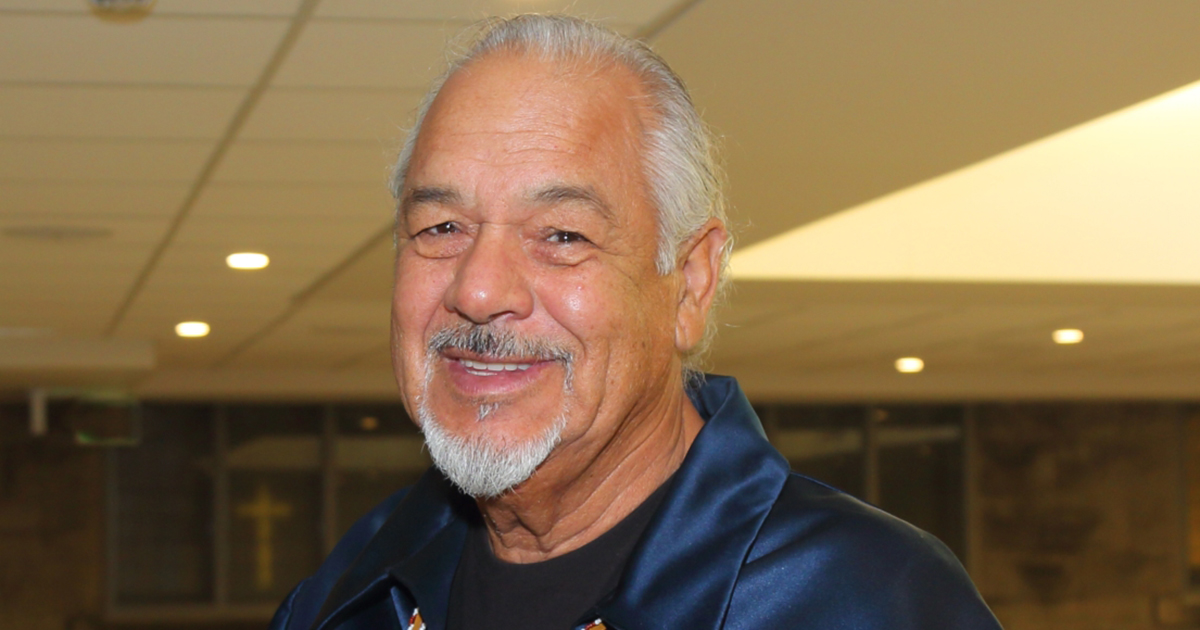

Indigenous spirituality has a powerful new voice at Christ Church Cathedral Ottawa.

In a historic appointment, local Indigenous spiritual leader Albert Dumont has been named Algonquin Spiritual Teacher in Residence for a two-year term at the cathedral. During his term, Dumont will help educate members of the cathedral community on traditional Indigenous spirituality, while deepening the relationship between the Diocese of Ottawa and the Algonquin nation upon whose unceded territory most of the diocese sits.

Dumont’s appointment marks the first time that a non-Christian Indigenous teacher in residence has been assigned to a cathedral of the Anglican Church of Canada.

“I see it as very important,” Dumont said of his new role. “To me, it’s an opportunity for people to know something about the Algonquin Anishinaabe in unsurrendered land.”

“There are people who really don’t know anything about the original inhabitants of this country,” he added. “They’re curious, and they want to know some details or some information about it. I’m going to be doing that … I’ll be happy to speak wherever they want about that relationship that’s been established now.”

The Very Rev. Shane Parker, dean of Christ Church Cathedral, appointed Dumont as Algonquin spiritual teacher in residence. The appointment came with the full support of Bishop John Chapman, as well as Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Chief Jean Guy Whiteduck.

Both Dumont and Parker highlighted the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as a crucial impetus for the appointment. The recommendations included recognition of the equal value of Indigenous spirituality.

“Albert is not a Christian,” Parker said. “He is an Algonquin man who has been shaped by the spirituality of his community, of his ancestors, throughout his life. I feel that having him in the cathedral will help us to understand Algonquin spirituality in particular, but [also] Indigenous spirituality in the context of a relationship, because I believe at the heart of reconciliation is developing a meaningful relationship between non-Indigenous and Indigenous people.

“Having Albert at cathedral signals our mutual concern … to learn and to share from one another’s spiritual traditions, and recognize them as equivalent.”

Confronting racism

Born in 1950, Dumont grew up in a reserve in Pontiac County in the Ottawa Valley. His father worked at a lumber camp for part of the year, and in order to leave the reserve, had to apply for a pass from a white Indian agent.

At this time, Indigenous people were also not allowed to vote in Canada, and practicing their own spiritual traditions was illegal.

“My parents were both honest, hardworking … Christian people, but they couldn’t leave the reserve without the pass,” Dumont said. “And it’s not they didn’t have any interest in Indigenous spiritualties. But if they would have, that would have been a crime.”

Dumont himself was a Christian until he was 12 years old. However, it was the racism from his teachers, fellow students, and community at large that gradually pushed him away.

To Dumont, it was “spiritually unacceptable” to see the very people who were cruel and vicious to him and his loved ones—simply due to their Indigenous ancestry—receive the Holy Communion.

“Whenever we first moved to [a] town, some people—thankfully, not all people, but there was a minority … people in the town who didn’t want us there—they’d tell us to go back where we came from. Even though where we were living was where Algonquins or the Anishinaabe had been living for many thousands of years … they told us to go back where we came from,” recalls Dumont.

Instead, he found refuge in the forest. On many days Dumont would pack a lunch and leave home in the early morning, not returning from the woods until dark.

“From that early age, I really connected with the forest … I just knew that I was at peace there, and I didn’t have to worry about racism or that kind of thing,” he said.

‘I identify with the grassroots of the Indigenous community’

Growing up, Dumont’s role models were his parents. His mother had 13 children, and together with his father, raised 11 into adulthood. Tragically, two of his brothers died in the 1940s.

Comparing Algonquin Anishinaabe traditions with Christianity as presented by European settlers, Dumont pointed to a major difference between the two belief systems, in that the “original spirituality of this land” emerged from a matriarchal society.

In the traditional Indigenous belief systems of his community, he said, “women had a lot of say in what went on in their family and in their community and in their nation. The viewpoints of women were very respected and honoured.” His own mother had a strong leadership role in his family, often taking charge of how money was spent and how the children would be disciplined.

Over the course of his life, Dumont has lived with chronic pain, and overcome a struggle with alcohol.

“The pain I live with allows me to identify with the pain of people who come to me who are in some form of emotional distress,” he said. “My past is one of bad addiction problems. I overcame the cancer that alcohol was for me. I can help people recover from the ugliness of destructive addictions. […] I identify with the grassroots of the Indigenous community. They know my heart as I know theirs.”

Role as teacher in residence

For many years, Dumont worked as a bricklayer. However, it is his storytelling abilities and knowledge of Algonquin traditions that eventually led to him working as a spiritual advisor for Corrections Canada at “a very violent prison”, as well as for the local parole board.

In this new capacity as Algonquin spiritual teacher in residence at Christ Church Cathedral, Dumont will share his knowledge wherever it is needed.

Potential areas may include spending time with Anglicans engaged in music ministry, meeting with Anglican clergy to teach Indigenous spirituality, and helping the cathedral reach out to ecumenical and interfaith spiritual leaders.

“His formation as a man who’s well-versed in the spirituality of his people has tremendous depth to it,” Parker said of Dumont. “Just at a personal level, I recognize him as someone who is a mature spiritual guide, a mature spiritual leader, and certainly his community and the wider community recognizes that as well.”

Albert Dumont is very committed to his new role at the cathedral, and looks forward to what lies ahead.

“I’m definitely going to do everything I can to help out, let’s put it that way.”

Interested in keeping up-to-date on news, opinion, events and resources from the Anglican Church of Canada? Sign up for our email alerts .