All Christians must work together to end corporal punishment of children, beginning with the repeal of a Canadian federal law permitting it.

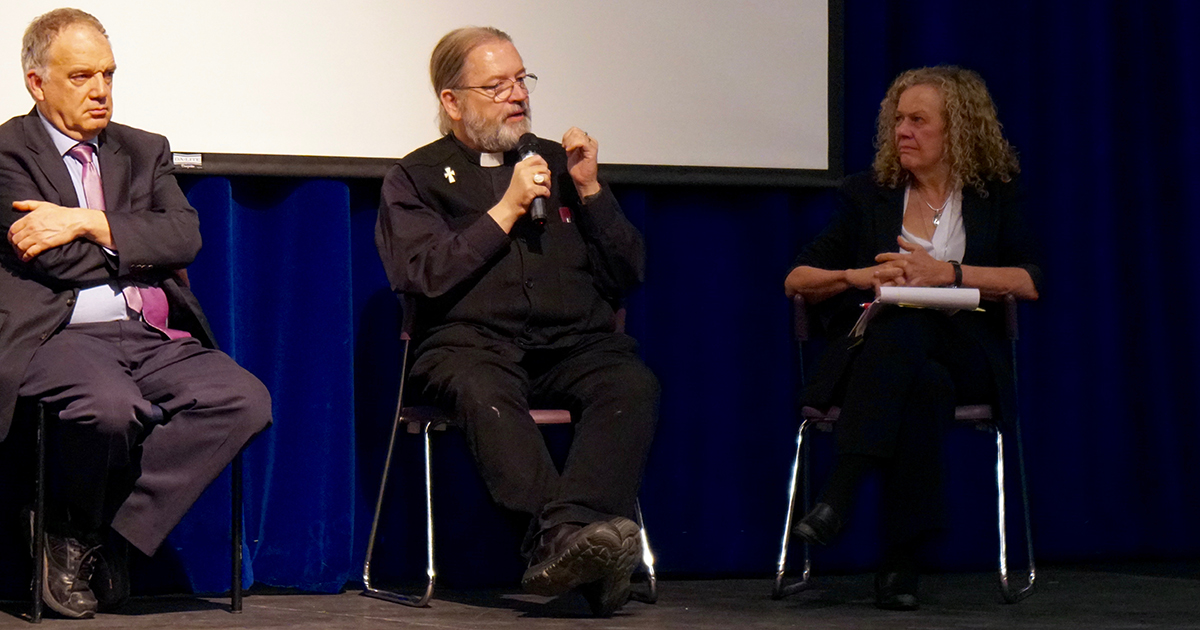

That was the key message coming out of a free public lecture, The Road to Reconciliation and the Protection of Children, held on Oct. 20 at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. Bringing together speakers from the religion and public health fields, the event focused on Call to Action No. 6 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which calls for the repeal of Section 43 of the Criminal Code of Canada—a section that legally defends the use of physical punishment by adults to correct a child’s behaviour.

In exploring the theology of childhood, the lecture linked ending corporal punishment of children with reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples of Canada.

One of the featured speakers was National Indigenous Anglican Bishop Mark MacDonald, who spoke on the role of the church in the residential school system and the road to reconciliation. Physical abuse of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children was a recurring issue at residential schools, many of which were run by the government and churches, including the Anglican Church of Canada.

“Section 43 of the Criminal Code is a living and dangerous remnant of the system that caused such damage to Indigenous Peoples,” Bishop MacDonald said. “Its repeal not only addresses the damage of the past, it safeguards the future of Indigenous children by removing the justification for the use of force in the discipline of children.”

Honouring the dignity of children

The idea to host the public lecture arose out of discussions at Queen’s University within the School of Religion and Department of Public Health Sciences.

The Rev. Dr. Valerie Michaelson, post-doctoral fellow and a researcher in both fields, had long been aware of evidence outlining the negative effects of hitting children in terms of their mental and physical health. She was also aware that many of the most fervent supporters of corporal punishment in Canada based their views on a general interpretation of the Old Testament.

Examining the TRC Calls to Action shortly after their publication, Michaelson realized that corporal punishment of children was at once a theological, Indigenous, and public health issue.

“I think what the TRC has shown us is that for centuries now in Canada, the church has often been on the wrong side of protecting children, the wrong side of history,” she said. “And I don’t want to say that lightly, because the church has actually made some wonderful contributions to child well-being as well.”

“We’re now having a chance to be part of reconciliation,” she added. “And we’re hoping that through this, we can invite the church to join a conversation about what a different theological message would look like that would really honour the full dignity of children.”

Rationale for repeal

Dr. Joan Durrant, a professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba whose research focuses on the physical maltreatment of children, said that Section 43 gives “a green light to parents to hit their children, and we know that that only brings negative things with it.”

For decades, researchers have known that corporal punishment of children predicts a wide variety of detrimental outcomes later in life, such as higher levels of aggression and anti-social behaviour, poorer mental health, more negative relationships with parents, and slower cognitive ability.

By contrast, Durrant said, there is “literally no evidence—none” for any long-term benefits associated with physically punishing children.

“There’s never, ever been any study that’s found a long-term positive outcome,” she noted. “The only thing that parents might consider positive is that the child might comply in the seconds following being smacked. But even that is unreliable, because a lot of times, children are hit for things they can’t actually control,” such as not being able to sit still.

Though hitting children may cause them to correct their behaviour in the very short term, Durrant said, in the long term it leads to a loss of trust as children avoid the parents who are causing them pain. Many experience greater trepidation towards touching and exploring their environments, which in turn leads to slower brain development.

In the most tragic cases, parents resorting to physical punishment have inadvertently killed their children.

“It’s these very common, everyday kinds of situations, where parents think that hitting is going to help, that lead so tragically to horrendous kinds of outcomes that they’re never anticipated, never wanted,” Durrant said. “But once you start hitting, you’ve raised the stakes, because anybody who’s hit will either strike back in self-defence or withdraw and run away, and not do what the person hitting them wants them to do.”

The challenge of biblical interpretation

Another featured speaker at the Queen’s lecture was Dr. Marcia Bunge, professor of religion and Bernhardson Distinguished Chair of Lutheran Studies at Gustavus Adolphus College, who spoke on the paradoxical nature of biblically-based theologies of childhood. The Rev. Dr. William Morrow, an Old Testament scholar in the School of Religion at Queen’s, also touched on similar topics during a subsequent panel discussion.

From the perspective of religious scholarship, corporal punishment strikes right to the heart of how Christians should interpret Scripture. Though the oft-quoted phrase “Spare the rod, spoil the child” never actually appears in the Bible, Morrow acknowledged that “that sentiment is certainly conveyed in the Book of Proverbs.”

“There are a number of passages in the Book of Proverbs that advise, or some people would say, even require parents to use corporal punishment against their children,” Morrow said.

He contends that no one passage in the Bible outright forbids the use of physical punishment against children. In the Book of Proverbs, children have essentially the same status of slaves, being subordinate to parents rather than masters.

Morrow drew a comparison with slavery as the “classic example” of an issue where Christians have been compelled to modify their interpretations of the Bible by finding larger “redemptive paradigms”.

“Gradually over time, Christian communities have come to accept that there are redemptive forces in the Scriptures, which suggest that owning slaves and being faithful to the gospels is not really in keeping with what Jesus and in fact the entire biblical canon’s redemptive paradigms were really trying to suggest or point to or vindicate,” Morrow said.

“The question that emerges for the church [regarding corporal punishment of children] is twofold, I think,” he added. “First it is how to genuinely stand up for the child in our society, and the second is … how to respond in a responsible way, in a pastoral way, to the calls for reconciliation from the TRC.

“I think that with respect to the Scriptures, you’re going to have a span of attitudes towards that, because although the church owns the Scripture as an authority, it has to balance that authority against other authorities.”

Towards a new theology of childhood

Organizers of the Queen’s event hope to spark a wider conversation about how to safeguard children and promote reconciliation through a new theology of childhood.

Beyond calling on the government to repeal Section 43, a theological statement that emerged from the event calls on Christians to work together to promote healthy and non-violent approaches to disciplining children; to address the disproportionate harm experienced by Indigenous children and youth; to increase awareness of the impact of violence; to be active in the protection of children; and to endorse the Joint Statement on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth.

Numerous Anglican leaders have endorsed the theological statement, including Bishop MacDonald, General Secretary Michael Thompson, and Bishop Riscylla Shaw of the Diocese of Toronto, along with representatives of the United, Presbyterian, and Methodist churches.

“I hope that we will start a conversation in the Canadian church … Call to Action 6 is not one that’s marked for the church, and so we would like to see that become part of our reconciliation story,” Michaelson said.

“We’d also like to see a much more dynamic and multidimensional and theologically rigorous conversation about children emerge. We’d like to do something that’s actually protective and helpful for all children in Canada, including Indigenous children, but including all children … Our hope is that our work on this makes the church [and] makes Canada a better place for children to grow up strong and whole.”

Interested in keeping up-to-date on news, opinion, events and resources from the Anglican Church of Canada? Sign up for our email alerts .